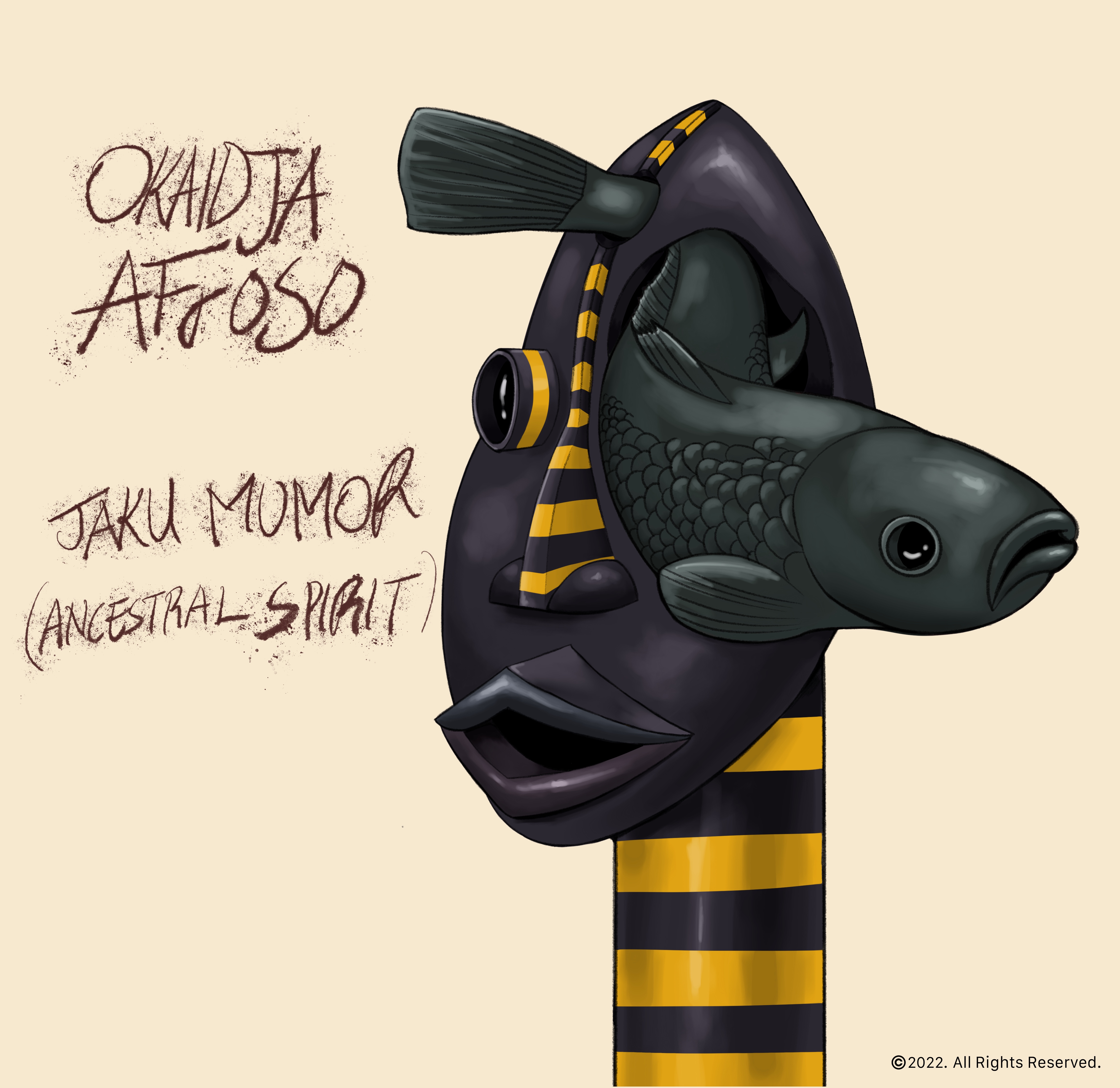

Okaidja Afroso

Wednesday, September 27 / 7:30pm

On sale now! Buy individual tickets or as part of the Mix 4 subscription package (15% off and complimentary parking) along with three other shows of your choice here.

Okaidja Afroso's distinct musical sound hails from the shores of Ghana, combining ancestral traditions and contemporary African music. His Jaku Mumor project dives into his cultural roots by collaborating with Gadangme fishermen to share the full artistry of their a cappella singing and chants that awaken the spirit of the human soul.

His artistry is grounded in traditional dance & rhythms with modern harmonies & updated lyrics. The performance includes footage captured in Ghana with the fishermen. Segments of the film, including singing and interviews, are incorporated into the live performance. One of the main themes of the program is the exploration of indigenous views on the element of Water, the sanctity of Fish, and the role of music, dance, and storytelling in Gadangme culture. Okaidja will use this opportunity to foster conversations about the challenges facing indigenous communities across the globe, such as the impact of rising seawater levels around fishing communities, as well as the effects economic development has on cultural preservation. Through this project, Okaidja hopes to learn and share indigenous resiliency practices or methods both for the sake of the American indigenous community and for him to bring back to Ghana and share with the Gadangme fishermen.

About Okaidja Afroso:

Okaidja Afroso comes from a family of musicians and storytellers in the fishing village of Kokrobite on Ghana’s west coast. As a boy, he worked with fishermen who sang a capella as they worked, and he passed long days learning songs of the great sea. At 19 he became a principal dancer with the Ghana Dance Ensemble in Accra. In 1999 he was invited to Portland, Oregon by the late worldbeat master Obo Addy to join his team of musicians and dancers to help promote West African culture to audiences throughout the Pacific Northwest. In 25 years of touring and performing Okaidja appeared in diverse venues from small fishing villages in the Canadian Arctic to the Kennedy Center in New York City, and he has spent countless hours in classrooms across the U.S. teaching children about Ghanaian culture and arts through educational outreach programs.

After many years with Obo Addy touring and facilitating African drumming/dancing workshops, master classes, lecture demonstrations, school assemblies and onstage performances, Okaidja decided to branch out on his own to fulfill his own creative ambitions. His distinctive performing style extends ancestral traditions and creates a contemporary African oral tradition combining percussion, guitar, dance and native language vocals. His songs convey a whole spectrum of experiences – joy, harmony, tragedy and hope – that embrace the rich complexity of the integrated world we inhabit.

Having produced four albums, Okaidja has also been commissioned to provide music for dance and theater productions. The Los Angeles-based dance company “Jacob Jonas the Company” commissioned him to compose original music for their piece “Crash”. Portland Repertory Theatre asked him to arrange the gospel tune “Children Go Where I Send Thee” for playwright Paula Volgel’s “Civil War Christmas”. For that task, he reached deeply into his background to incorporate the Ghanaian fishermen's singing style. He also added his own vocal colors that drew from his research into the music of the African Diaspora to marry the essence of African and African American music.

Says Okaidja, “Although I am an African, in America I’m simply a Black man, and I share the Black experience of sometimes receiving silent suspicion and hostility, at least until I speak. At that point, my origin may be of interest, or I may be dismissed as simply a jungle-dweller from the depths of the dark continent. In any case, I share the experience of prejudice with African Americans."

"I have also discovered that both Africans and African Americans lack accurate education about each other’s historical experiences. As a result, most Africans have little to no knowledge about the Trans-Atlantic slave trade and how it impacts African Americans, while African Americans learn about Africa through Hollywood movies which portray Africa as a land with a tremendous lack of resources instead of a vibrant continent of great cultural heritage to be proud of."

"I also had the experience of making a compelling connection with indigenous people in Alaska through the ancient language of drumming and I’ve wanted to create more and deeper connections with Native Americans. I’ve gradually become aware of similarities in how indigenous Africans and indigenous Americans relate to the natural world and the way that arts cultivate and express this relationship. Both peoples have suffered due to colonization. But I am encouraged to see that “traditional ecological knowledge” is now being recognized as valid by the American government and academic entities. I am eager to learn how this shift has come about and to share our mutual experiences in that regard."

"As a person of both Black and Indigenous identity, I am in a unique position to make a positive contribution to this period of racial reckoning through using the power of the arts to help people unite and heal."

Jaku Mumor (Ancestral Spirit)